Each time the news flashes the words “abducted by gunmen”, it tears through the fragile calm of Nigeria’s collective consciousness. A doctor on duty, a student walking to class, a farmer returning home, a clergyman mid-sermon—each name added to the growing list of victims reshapes the country’s sense of safety. Abduction has ceased to be a distant nightmare; it now stalks ordinary lives with unnerving consistency.

The nation’s landscape of fear has grown familiar with the sound of breaking stories about missing people. From the creeks of the Niger Delta to the highways of Kaduna, from the outskirts of Abuja to the forests of Zamfara, kidnapping has become a grim currency of survival for criminal groups. Every case reads like a rerun—armed men emerging from the dark, vehicles stopped at gunpoint, families left in agony, and a desperate race to raise ransom. The repetition has dulled empathy, but the horror remains unyielding.

Communities now live with a quiet resignation, adjusting daily habits around the fear of disappearance. Parents escort children to school in groups, transporters avoid certain routes after sunset, and churches shorten evening services. The shared trauma of insecurity has knitted together people across religion, tribe, and class—not in unity, but in mutual dread. It is no longer about “if” someone will be kidnapped, but “who” and “when.”

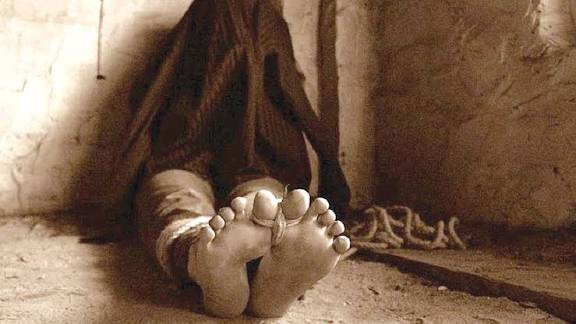

Survivors’ stories reveal the psychological toll behind the statistics. A nurse from Katsina recalled how her captors blindfolded her for days, forcing her to navigate survival by sound and smell. Another victim, a student abducted along the Abuja–Kaduna highway, said he began to forget his own name after weeks of isolation and fear. For them, life after freedom is a return to bodies that no longer feel safe. The scars are invisible but permanent.

The economic dimension of this menace cannot be ignored. Kidnapping has evolved into a shadow industry—one that thrives on the failures of the system meant to prevent it. Bandit groups collect ransoms in millions, while security agencies remain underfunded, underequipped, and sometimes complicit. The consequence is a thriving ecosystem of negotiators, informants, and middlemen who profit from human suffering. Villagers are now forced to contribute to ransom pools, knowing that refusing might doom their loved ones.

Government responses often come too late or too weak. Press statements promise investigations that fade before arrests are made. Policemen in rural outposts, themselves underpaid and poorly armed, often serve as first responders to crises they can barely contain. Each rescue mission that succeeds is overshadowed by dozens that never happen. As a result, the public trust in law enforcement continues to erode. Many now prefer paying ransom to waiting for the state to act.

Politically, the kidnapping epidemic has become a mirror reflecting leadership failure. Governors call for community policing, while citizens accuse them of detachment. Federal officials cite funding gaps, while critics point to corruption and disorganization. What gets lost between these competing narratives are the lives reduced to bargaining chips. When the protection of citizens becomes negotiable, governance itself loses moral ground.

The human cost extends far beyond the victims. Families disintegrate under the weight of fear. Businesses relocate or close. Students drop out of school after repeated abductions in hostels and classrooms. The trauma ripples through communities, reshaping social behavior and economic activity. Rural areas, once vibrant with farming, are now ghost settlements. Schools in several states remain shut, leaving an entire generation without education or hope.

Religious leaders have not been spared. From Catholic priests to Muslim scholars, clergy abductions expose the indiscriminate nature of this violence. Their kidnappers understand that taking a spiritual leader guarantees attention, emotion, and donations from followers. It also fractures moral confidence, forcing faith communities to confront their vulnerability. The pulpit and the prayer mat are no longer sanctuaries.

Social media amplifies the despair, turning each abduction into a digital vigil. Hashtags emerge, fade, and reappear, but the cycle never truly ends. Behind every trending story lies a family negotiating in whispers, mortgaging their future to buy back their present. These platforms have become both a cry for help and a memorial ground for those never returned.

Security experts warn that the persistence of kidnapping signals a deeper decay—the normalization of violence as livelihood. The nation’s unemployed youth population, coupled with porous borders and weak intelligence systems, creates a fertile ground for organized crime. Rural poverty and ungoverned spaces feed the cycle. Without comprehensive reform, the country risks turning abduction into a generational enterprise.

Public reaction oscillates between outrage and fatigue. People have seen too much to remain shocked, yet too little change to feel hopeful. Candlelight processions fade faster than the memories of the missing. A nation that once demanded justice has learned to whisper its grief. Silence has become both a coping mechanism and an indictment.

The need for systemic reform grows more urgent by the day. Strengthening local intelligence networks, improving police response time, investing in forensic capacity, and addressing unemployment are not just policy options—they are moral obligations. The government’s promise to secure lives must evolve beyond rhetoric into measurable action. Without that transformation, every abduction will continue to echo the same message: no one is safe.

Communities have shown resilience where the state has failed. Local vigilante groups, neighborhood watch teams, and traditional rulers are stepping into the vacuum. Their courage, however, cannot replace institutional structure. Without coordinated security reform, these efforts remain stopgaps—brave but brittle solutions to a national crisis.

Nigeria‘s fight against kidnapping is not just a battle for safety but a struggle for identity. A country that cannot protect its people loses the right to claim stability. The collective trauma of abduction is reshaping national consciousness, breeding cynicism and distrust. To heal, Nigeria must not only pursue the kidnappers but also rebuild the belief that human life is sacred and secure.

Every new story of kidnapping tears open an old wound. It reminds citizens that the boundary between safety and peril is paper-thin. It reminds leaders that security is not a privilege to be rationed, but a promise to be fulfilled. It reminds the world that beneath every headline is a family still waiting, praying, and hoping for return. Until those reminders stop coming, the nation will remain on edge—haunted by the same refrain that has outlived too many administrations: no one is truly safe.

Samuel Dayo creates high-quality content that resonates with readers. His work spans governance, culture, business, and tech.